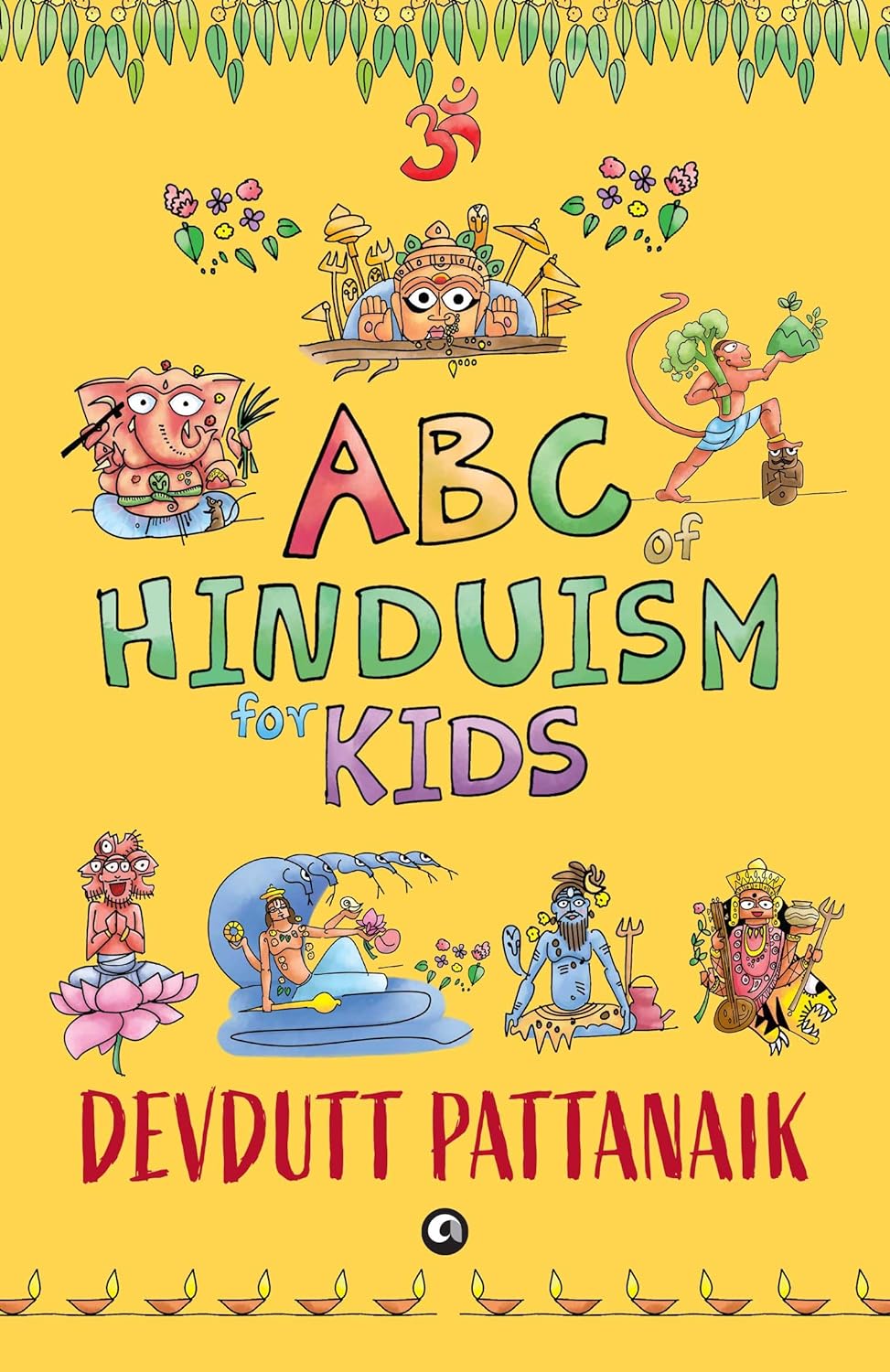

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are presented in the synagogue, church, and mosque as godʼs instructions to humanity on how to live life. In recent times, a new group of Hindu missionaries, who first appeared during Indiaʼs national movement, is following the same path of instruction-based ‘satsangsʼ; but it is hardly institutional, for Hinduism is not commandment-based. It is story-based; and stories, unlike instructions, appeal more to emotions than actions.

Animals do not tell each other stories. Humans do — for entertainment, for propaganda, for memory and history transmission, and, most importantly, for meaning. Stories transmitted over generations serve as the glue of a community.

This is why Christianity is established by two stories that are repeated twice a year: in springtime, the story of the crucifixion of Jesus and his resurrection; and in winter, the story of his birth. In Shia Islam, the story that glues the people together is the martyrdom of the Prophetʼs family. The ritual of Ramzan is a reminder of a story of when the angel of God communicated Godʼs will to Muhammad, the final prophet for Muslims.

About 2000 years ago, taking a cue from the popularity of Buddhist Jatakas, Brahmins — then facing an existential threat — realised that to survive, they have to be relevant to the masses, and to be relevant to the masses they have to communicate the Vedic idea, and the best way to do so is through storytelling. So, they created epic stories: stories of Ram, stories of Krishna, inspired by probable events of 1000 BC, and stories of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Such was their popularity that they came to be referred to as the fifth Veda.

These stories were narrated or performed as per the principles of Natyashastra of Bharata. Natyashastra, or the science of theatre, explains how to perform a story. It is said to have been inspired by dialogues from the Rig Veda, music from the Sama Veda, gestures from the Yajur Veda, and sets and costumes from the Atharva Veda. In South India, we have the famous theatre halls (Kuthambalam) within temples for the Brahmins, and street performances (Therukuthu) on the streets. In North India, there is the Ram-leela and Rasa-leela of the Gangetic plains, which ensured the popularity of Hinduism in that part of the subcontinent. In Odisha, there is the famous Prahalada Nataka. In the foothills of the Himalayas, there is the famous Pandav Lila.

What distinguishes Indian storytelling is the emphasis on the aesthetic experience (rasa). The story is supposed to churn our mind and produce sensations (rasa) and emotions (bhava), which hopefully grants us insight (darshan) into the human condition. That is the purpose of the plot, the character, and the drama. Hindu storytelling works not at a cognitive level (laws to be followed) but at a visceral, emotional level (emotions to be experienced). Hindu ritual is all about the emotions and the mood (rasa, bhava) evoked.

Many believe Indian theatre tradition was influenced by Greek drama which was introduced by Indo-Greek Yavana kings who ruled the Northwest in the wake of Alexanderʼs invasion in the 3rd century BC. However, the Greeks focussed on two emotions: comic and tragic. Hindu storytelling presents a whole range of emotions: the nava rasa, or nine moods, from the romantic (madhurya) and erotic (shringara) to the disgusting (vibhatsa) to the calm (shanta).

The story is called katha, kahani, which means ‘what happened exactlyʼ. The characters are called patra, which means ‘utensilʼ, through which rasa and bhava are conveyed to the audience. The story can be equated with a meal that satisfies a hunger in the audience. What are we hungry for? Entertainment, at the very least. Insight, if we are lucky. The narration can be a snack, or a meal, providing one flavour and one texture, or many, sequentially or simultaneously.

Hindu investment in storytelling is huge. It was not simply a propaganda tool. It worked at many levels to communicate complex and refined ideas about the human condition. The Ramayana is a case in point. The epic begins with the story of Valmiki witnessing a hunter shooting an arrow that kills one of a pair of birds. The survivor circles her dead mate and cries piteously. Valmiki is filled with sorrow and rage, and he curses the hunter, who was simply doing his duty, providing for his family by following his hereditary vocation.

The event, thus, captures the tension between karma (the action and reaction of killing) and dharma (feeding oneʼs family). It is never told, but it is derived; and this theme recurs throughout the epic. In some episodes, Ram is the hunter shooting the bird (Vali, Ravana). At other times, he is the bird, being shot by the cruel arrows of life (Kaikeyiʼs ambition, Ravanaʼs trickery). No one tells you this. The storyteller gives you sight. You use your intelligence to gain insight, and reflect on your own life.

This is darshan, the Vedic key to witnessing the world, and giving meaning to your own life.