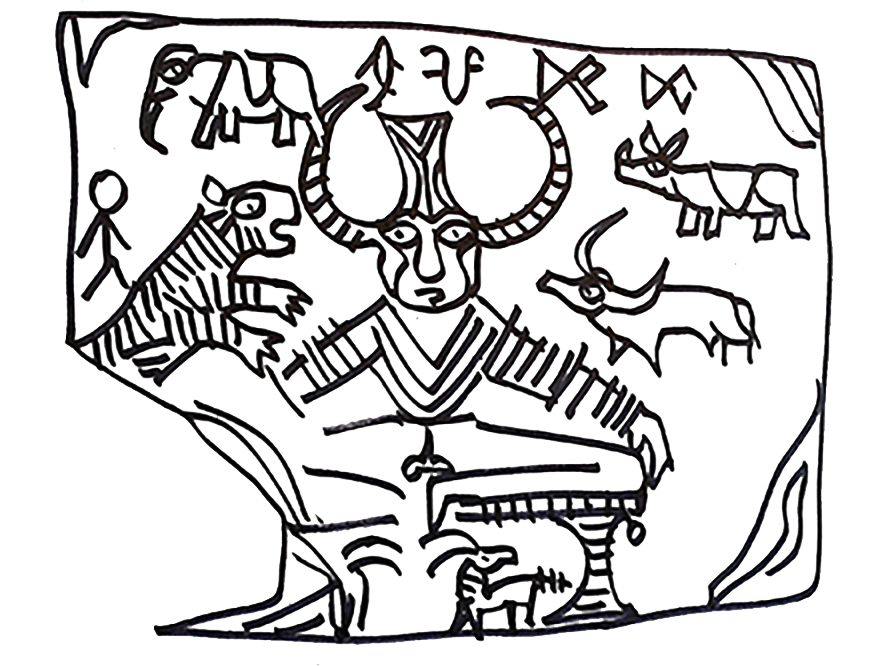

Harappan seals depict many monsters: unicorns, sphinx, and horned tigers, and these may have been inspired by their trading relations with West Asia. But unlike the green sphinx that has a lion’s body, the Harappan sphinx is a woman with a tiger’s body. The tiger body indicates the indigenous origin of the Harappan motif.

Nearly 1,500 years after the fall of Harappan cities, these mythical creatures reappear in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, along trade routes connecting the Gangetic plains to the western coast and to northwestern lands such as Gandhara. At sites such as Sanchi and Mathura, one finds Buddhist and Jain artworks, where sphinx-like creatures reappear alongside birds with human heads. They are shown as celestial beings arriving to pay homage to the monks and teachers, and do not seem to be of Indian origin.

Lions with wings and bird-like heads, known as griffin, are still popular in young adult fantasy novels, and are creatures from Persian mythology. Men with horse bodies, known as centaurs, are from Greek mythology. Such images are also found in the Bhaja Caves of Maharashtra’s Western Ghats, and are dated from 200 BCE to 300 CE. This was the time trade between India and West Asia was at an all-time high. Indo-Greeks (also called Yavana) had established cities in the Gandhara region. Their culture mingled with Persian culture, which in turn was influenced by Mesopotamian culture, and shaped much of Scythian and Parthian art. Temples of this region are full of fantastic beasts.

Migration to India

The Vedic corpus, composed between 1500 BCE and 500 BCE in the Indus and Ganga river basins, alludes to mythical creatures such as the three-headed serpent but lacks such fantastic imagery. There is no such creature in early Sangam poetry either. It is only in later Puranic literature that we encounter fabulous beings who are part-human and part-animal. Could this be the influence of Greek and Persian artists employed by Mauryan and Satavahana kings in their courts?

Around 300 CE, when the Roman Empire became Christian, artists who carved pagan gods were persecuted and many migrated east, finding patronage in Indo-Greek kingdoms, perhaps even in the western ports of India. Did they inspire the image of Narasimha, the lion-headed avatar of Vishnu, emerging from a pillar, perhaps a Persian pillar, to rescue a devotee? The Vedic antecedent of Narasimha’s story involves the asura Namuchi, who can only be killed by a weapon that is neither water nor air, prompting Indra to use foam. The story has no reference to a creature that is neither man nor animal.

Shiva’s bull Nandi is sometimes depicted as a bull-headed man, just like Durga’s enemy, the buffalo Mahishasura, is sometimes shown as a buffalo-headed man. But these cannot be classified as half-animal creatures. The most popular mythical creature in India is no doubt the multi-headed serpent or Naga, which is very indigenous. It is linked to fertility and wisdom, and found in the earliest Buddhist, Jain and Hindu art, protecting Buddha, Parsvanath and Vishnu. Another creature is the half human-half bird who sings, known as kinnara, though this image is more popular in Southeast Asia. While Greek myths show monsters as symbols of chaos, in Persian myths they seem to be guardians, and in India, they appear as symbols of grace and benevolence.

The Southern sphinx

In South India, we find images of the purusha-mriga, a man with the feet of a tiger, though sometimes he is shown with a lion’s mane. Interestingly, no such images exist in North India. In Tamil mythology, he is identified as Vyaghrapada, or the one with tiger feet, who collected forest flowers for Shiva. When offered a boon, he asked for protection for his feet from the thorns and sharp rocks on the forest floor. So he was given tiger feet.

Purusha-mriga is linked to Vishnu through a version of the Mahabharata found in a Tamil temple. The Pandavas were conducting a yagna and for it to succeed, they needed the presence of a purusha-mriga. When invited by Bhima, the forest creature presented a condition. ‘If I outrun you, I will eat you,’ said the beast. ‘But if you outrun me, then I will come for the ceremony.’ So the two raced towards Indraprastha. To help Bhima, Krishna gave him shiva-lingas to drop on the forest floor, which forced the purusha-mriga to stop and offer them forest flowers. The resulting delay would have been just enough to help Bhima win the race. But by Shiva’s grace, the purusha-mriga managed to catch Bhima just as he put one foot in Indraprastha.

Yudhishthira was called to judge the contest, and he declared that the purusha-mriga could eat that half of Bhima which was still in the forest. Yudhishthira’s fairness so impressed the beast that he decided to spare Bhima and attend the yagna. His presence brought fortune to the Pandavas, and since then, his image is often found on temple walls, gates, processional images and even in lamps of South Indian temples.