In 1898, William Peppé, a British engineer, excavated the Piprahwa stupa near Siddharthnagar in Uttar Pradesh (nine miles from Lumbini, the birthplace of Siddhartha Gautama), and found bone fragments, ashes, and hundreds of gems. The inscription claimed the bones were those of the Buddha himself. These relics were distributed to museums in India and abroad, but a portion of the gems stayed with Peppé’s family.

When Sotheby’s planned to auction them in Hong Kong in 2025, the Government of India objected, calling them part of its spiritual heritage. The sale was blocked, and eventually the Godrej Group acquired them and brought them back to the country for public display. A 2,200-year-old act of veneration was restored to its rightful place. This incident draws attention to the importance of stupas in ancient India.

The stupa has a long history. And it transformed over time, in form as well as content. In the beginning, the stupa was about the Buddha’s body. According to tradition, when the Buddha died, his body was cremated, his relics collected and divided into eight portions and enshrined in different stupas by kings and republics who wanted a share of his presence. Later, Ashoka redistributed these collections to 84,000 sites across India.

Across Southeast Asia — in Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand — there are many great stupas that claim to contain the relics of the Buddha, such as his hair, his nails, and his bone fragments. These were in great demand, exported along with manuscripts to China. Many believed stupas containing the relics had magical powers; they could cure ailments. By the 2nd century AD, stupas at Sanchi, Bharhut and Nagarjunakonda were decorated with elaborate railings and gates showing scenes from the life of the Buddha and the Jataka Tales.

A philosophical shift

By the 5th century AD, the Buddha was no longer only in bone and ash — he was in the teaching. Inside stupas, monks began placing stone and terracotta tablets inscribed with the Pratityasamutpada formula on dependent origination: “Of those phenomena which arise from causes, the Buddha has explained the causes, and also their cessation.” This was a philosophical shift — the stupa now enshrined wisdom, not just relics.

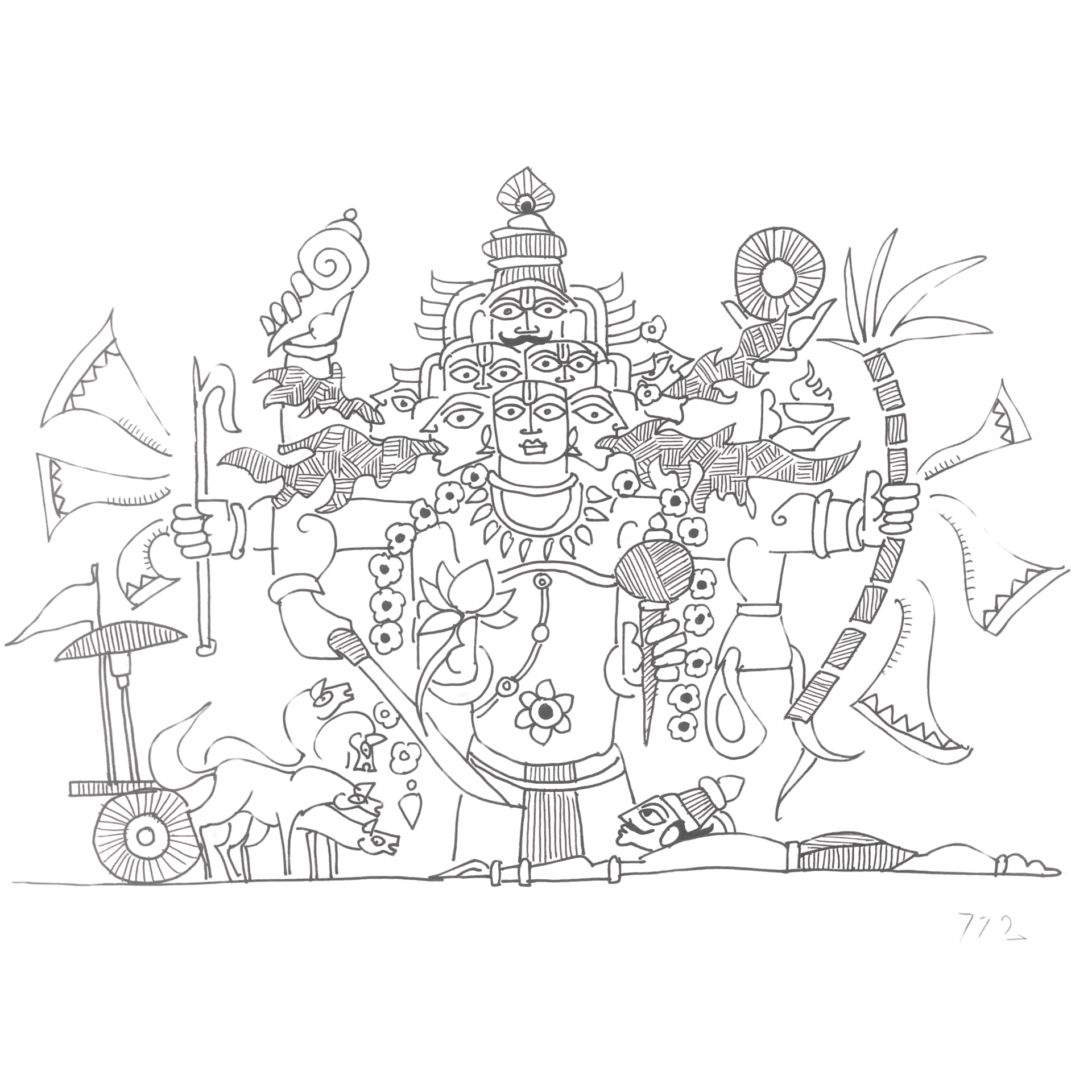

Seeing the dharma became the same as seeing the Buddha. This is when images of Buddha became common. Many bear the same formula carved on their base, turning the image into the “truth body” (dharmakaya) of the Buddha. The stupa thus became a container of word and image, of memory and meaning.

From the 7th century onwards, stupas started to hold dharani — protective spells promising not only merit but tangible benefits such as safety, prosperity, and heavenly rebirth for the dead. Mahayana texts (Buddhist scriptures) instructed donors to write these spells on copper, stone, or clay and deposit them inside stupas. At Udayagiri and Lalitgiri in Odisha, archaeologists have found several such inscribed plaques. The stupa was no longer passive; it was now a ritual engine radiating spiritual power.

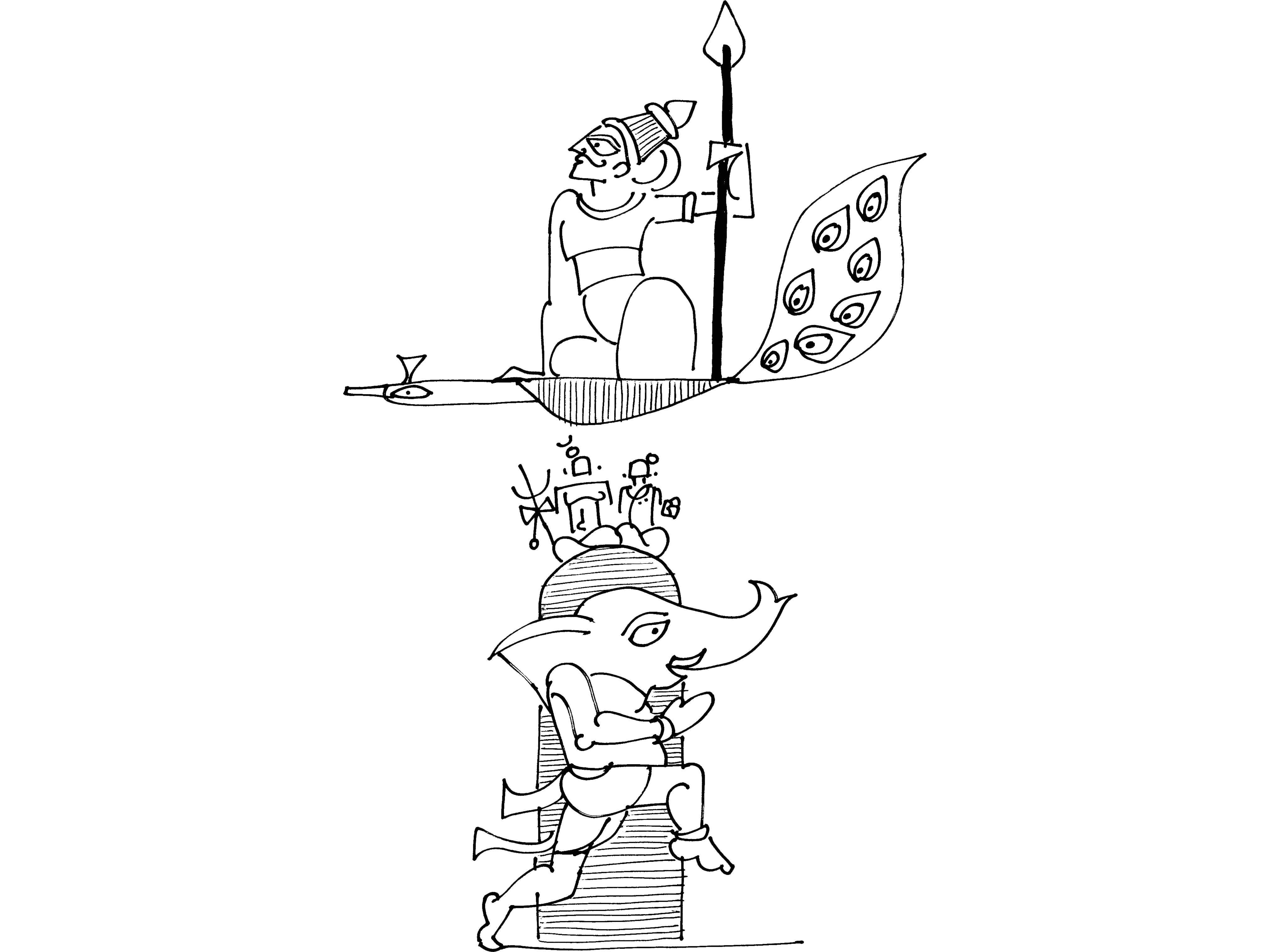

By the 8th-9th centuries AD, the stupa became a three-dimensional mandala, a cosmic diagram in brick and stone. The Mahastupa of Udayagiri, built on a high platform, contained four Tathagata Buddhas facing the cardinal directions, each flanked by paired Bodhisattvas — a direct reflection of the Garbhadhatu Mandala of the Mahavairocana Sutra (a core esoteric diagram). This was not merely a reliquary but a theatre for tantric visualisation, a space where monks and initiates could meditate on the cosmic Buddha Vairocana.

Evolution in the East

Through all these centuries, the chaitya-griha or prayer hall area remained the real centre of devotion. Votive stupas multiplied there, images of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas were consecrated, and new shrines kept being added. Buddhist teachers and even Buddhist kings were declared Bodhisattvas and their tombs were turned into stupas. They were seen as sites of mystical and occult power.

As Buddhism spread eastward from India, the stupa evolved in form and meaning. In China, it merged with native tower traditions to become the multi-storeyed pagoda, symbolising ascent towards enlightenment. In Korea and Japan, the pagoda became more slender, often built of wood or stone and serving as temple centrepieces. In Southeast Asia — Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Indonesia — the stupa grew taller and more ornate, such as Borobudur in Java, representing a cosmic mountain. While Indian stupas held relics, East and Southeast Asian versions emphasised visual symbolism, ritual circumambulation, and the merging of local architectural aesthetics.

The Piprahwa relics remind us that this is not just history. The stupa tradition is alive because the relic still matters — spiritually, culturally, even legally. India fought to stop their sale because they are not just objects, they are living heritage.