Originally Brahmins were simply transmitters of the Veda. Later, as keepers of dharma-shastra, they offered administrative services to kings. From the 10th century AD, they faced enormous competition from a rival caste group offering scribal, accounting and advisory services – the Kayasthas.

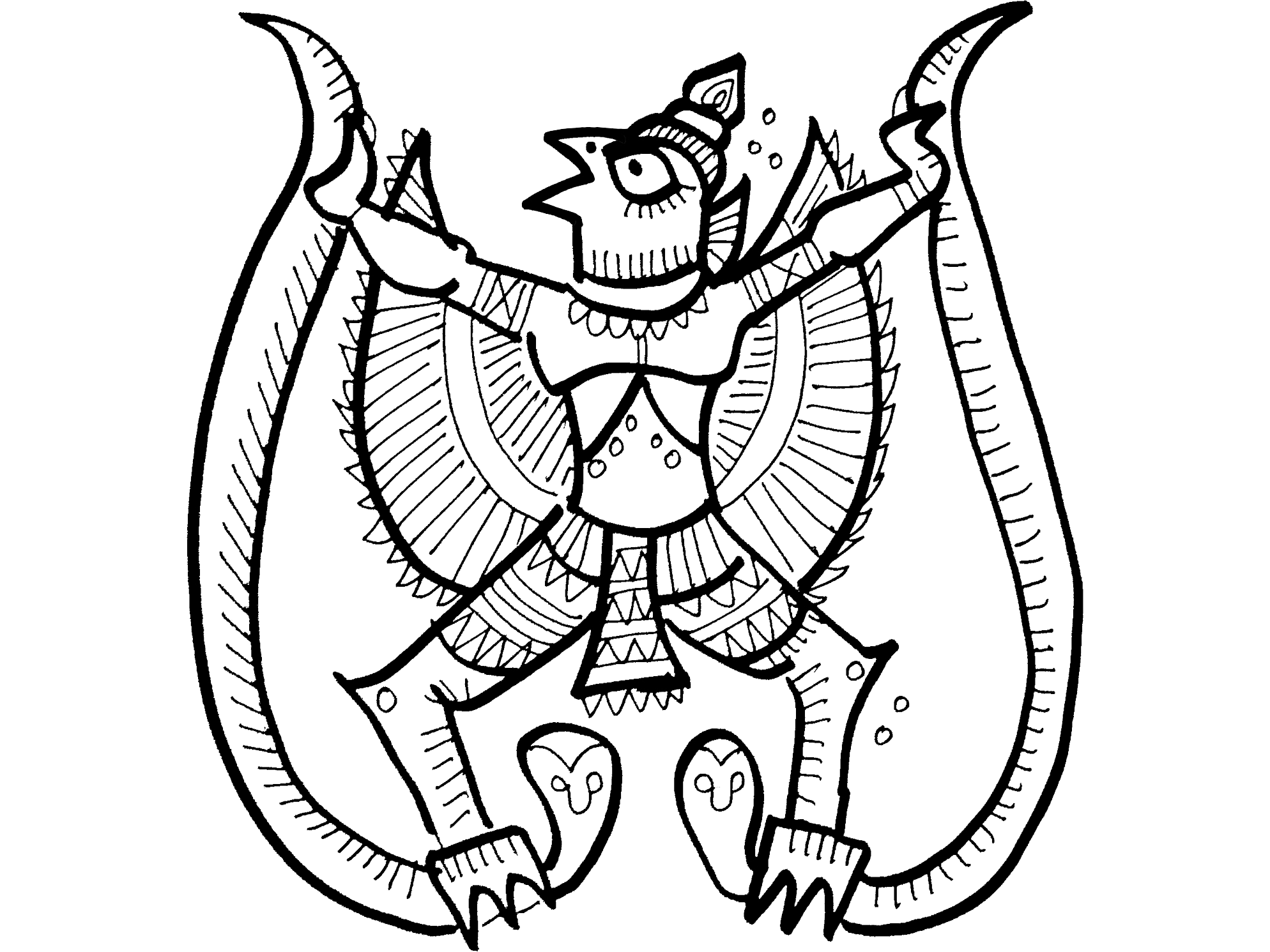

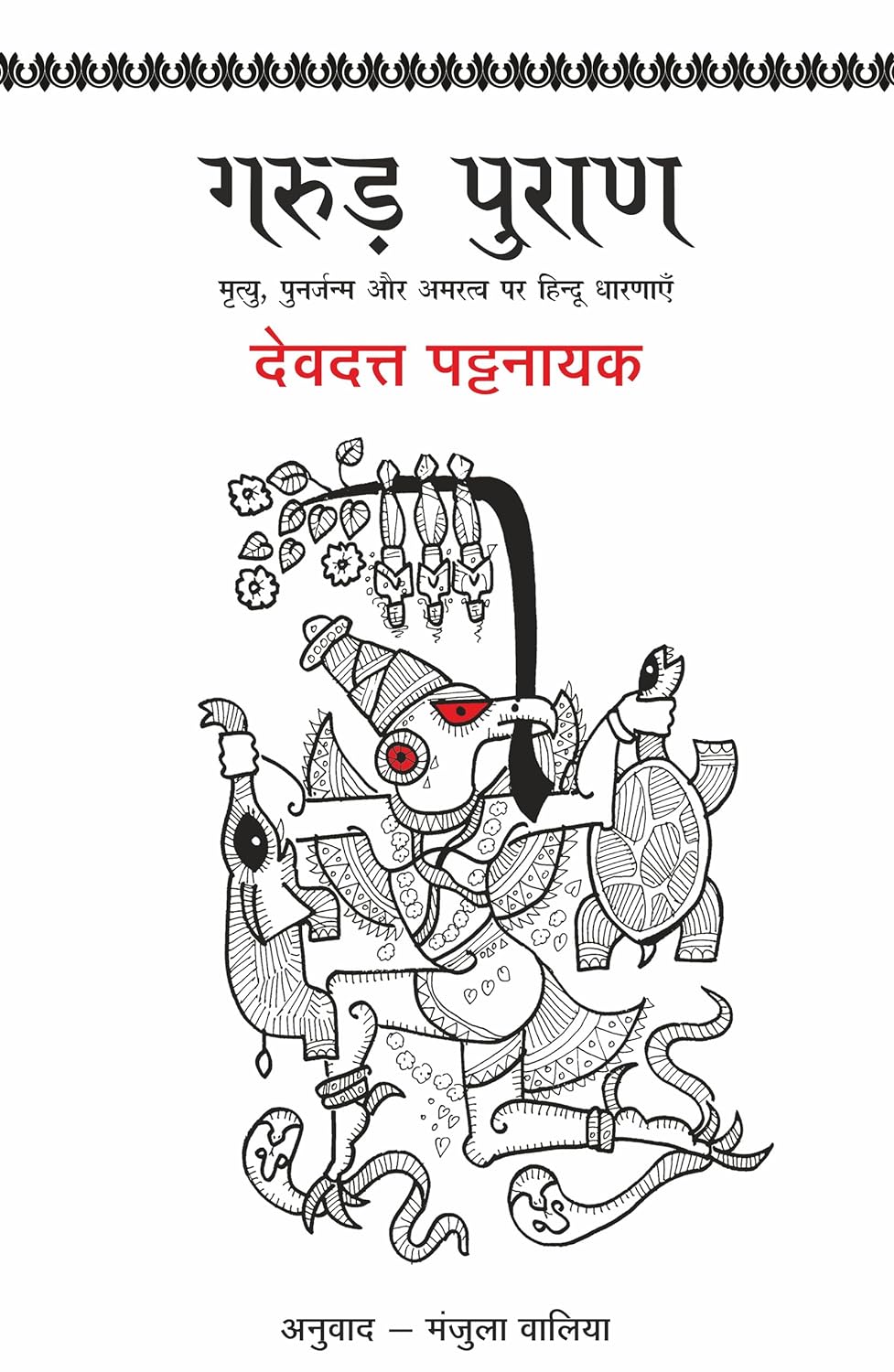

Brahmins had a ritually higher status as keepers of the Veda. Most curiously, the Kayastha claimed a defiantly opposite origin story. Brahmins could trace their descent to Brahma’s mind-born sons, the Rishis, including Manu, who listed the dharma (obligation) of all communities. Kayasthas claimed descent from Chitragupta, the record-keeper of Yama, the god of death, who is also known as Dharma, who ensures everyone repays their debt. While Brahmins claimed descent from visionaries, Kayasthas claimed descent from auditors. Brahma is visualised holding ritual implements in his hand; Chitragupta is visualised with a ledger book, a pen and an inkpot.

Who were the Kayasthas in the four-fold hierarchy of Manu’s world? To which varna did they belong, asked the British? Kayasthas argued that, like many prosperous communities, they were originally Brahmins or Kshatriyas. They were shunned by Brahmins because they ate meat like Kshatriyas. They were shunned by Kshatriyas because they chose the pen over the sword. Brahmins insisted the Kayasthas were Shudra, or service-providers.

When rulers changed, Kayasthas and Brahmins adapted, first learning Persian for the Sultans, then English for the British. The battles to gain access to the court were bitter. This was before the British introduced Civil Services Exams, open to all communities. The idea of merit-based bureaucracy was not a European one, but a Chinese one, instituted 1500 years ago, during the Tang era.

Spiritual Balance Sheet

Record keeping and accounting is at the core of any society. It supports (asti) the body (kaya) of the state. Yet, in Indian culture, greater value is given to Hindu mysticism (atma/maya/moksha) or to Hindu feudalism (jati/varna/bhakti). Stories involve mostly Brahmins (educated communities), Kshatriyas (aristocratic communities), and Chandalas (so-called impure communities). Hardly any attention is given to the economic side of Hinduism, the value placed on ideas such as debit, credit, land-grants, and accounts played a key role. We know more about poets than scribes.

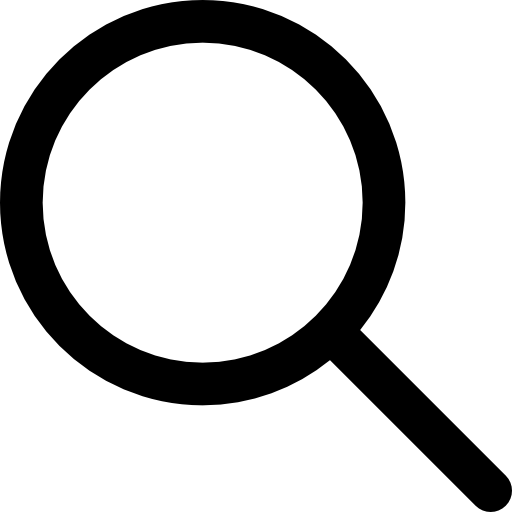

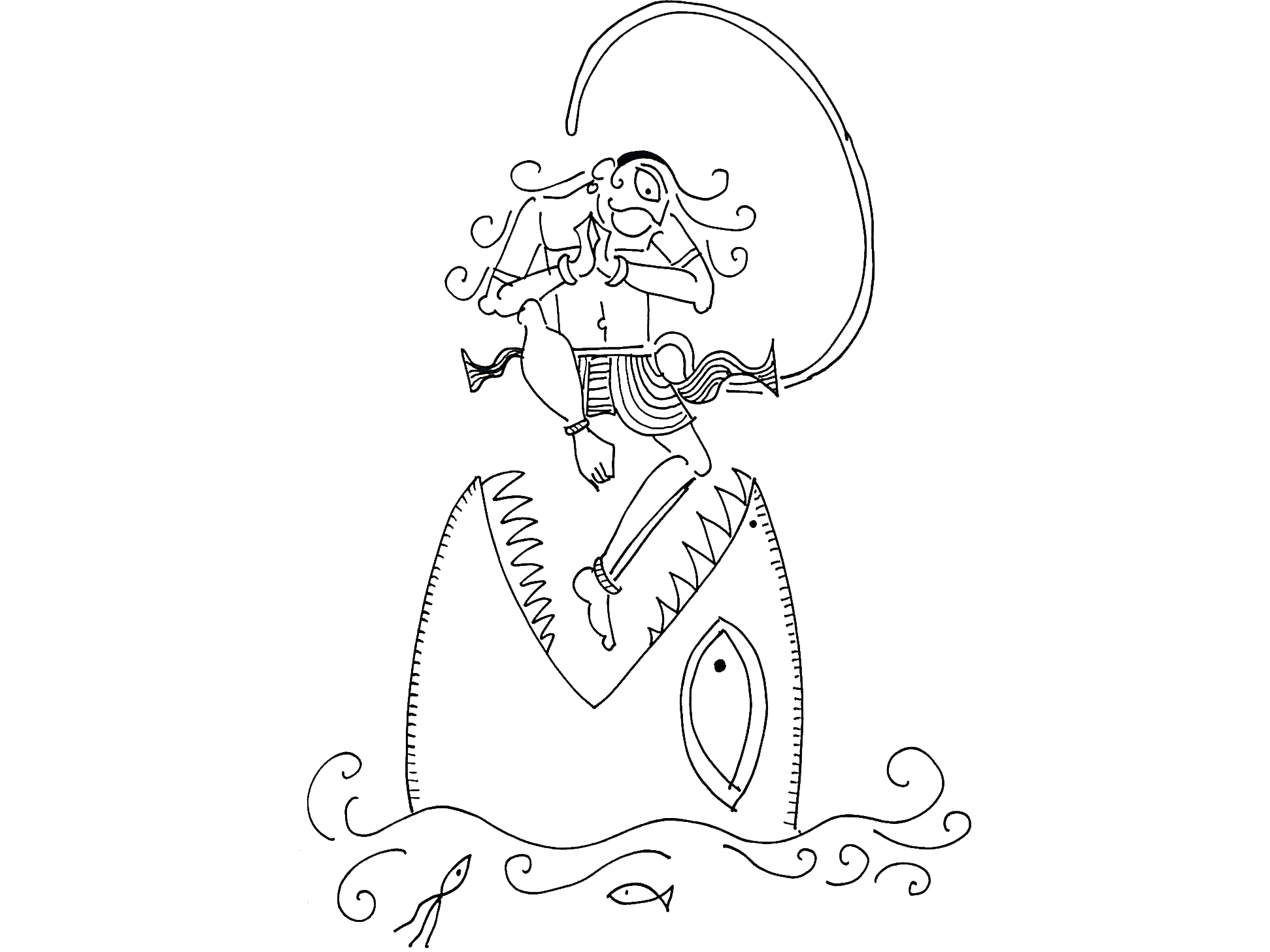

The world of balance sheets is in fact the world of karma: the world of debt and equities, of debit and credit, of snakes and ladders. Taking loans drags us to Naraka, hell. Investing in others lifts us to Swarga, paradise. Liberation happened when you repaid loans who owed others and wrote off all debts owed to you. This financial approach to religion put the spotlight on Yama, the god of death, and transformed him into the god who ensures rebirth as long as there are debts to repay. Yama is mentioned merely as god of death in Vedas; but in Mahabharata he becomes Dharma; and in Puranas, he has an entire office, in the land of the dead, full of scribes and accountants, managed by the ever-vigilant Chitragupta.

Tales of accountant-saints

The importance of accounting (not necessarily Kayastha) emerges in later Hindu bhakti literature, where many saints who work in royal treasuries are accused of embezzlement. God comes to their rescue.

From Tamil speaking lands comes the story of Manikavasagar whose military prowess so impressed the local king that he hired him as a soldier. Manikavasagar soon rose in rank and became the king’s confidante. The king once gave him money to buy horses, but on the way Manikavasagar encountered an ascetic who revealed to him the glory of Shiva. Inspired, Manikavasagar used the king’s money to build a temple of Shiva, incurring the king’s wrath. But Shiva protected him by turning jackals into horses.

From Kannada speaking lands, comes the story of Basavanna who was employed as an accountant to the royal treasury. He believed in equality for all communities, which naturally upset those who followed the caste system. The saint was famous for feeding sages who visited the city. His rivals complained that the accountant was misusing funds from the king’s treasury to fund his philanthropy. An inquiry was held. It was proven that the accountant had not misused the king’s funds. But the incident left a bad taste and the two parted ways.

From Telugu speaking lands, we learn of an accountant who built a temple of Ram, on the banks of River Godavari. He was accused of embezzlement and put in jail. As per one version, he was rescued by Ram himself, who paid his bail. In other stories, because the king had committed a crime against an innocent man, his fortunes dwindled. His kingdom was attacked by Mughals. The only way he could save himself was by getting back into divine grace. The only way he could do this was by releasing the accountant from prison.

All three stories reveal the power, hence vulnerability, of those who maintained (and so could easily manipulate) accounts, registers and records. Their documents could easily be weaponized, even against them. To survive, they needed the trust of insecure kings. And when that was not forthcoming, they needed the support of gods.