Published in Sunday Midday (Mumbai) on 29 Nov 2009.

The patterns are done only by women. And the material used was once rice flour but now synthetic powders, even paint, are being increasingly used. And for the busy household there are readymade sticker bright Rangolis.

Does this have any logical purpose? Yes, say the rationalists, who say the rice flour is meant to feed ants so they do not enter the house. Does it have any aesthetic purpose? Yes, it enables the homemakers make the house pretty. But that still does not explain why it has to be done every day, by women, at the doorway. That the practice becomes elaborate during festivals and rites of passage, indicates that this ritual is rooted in emotion, myth and magic.

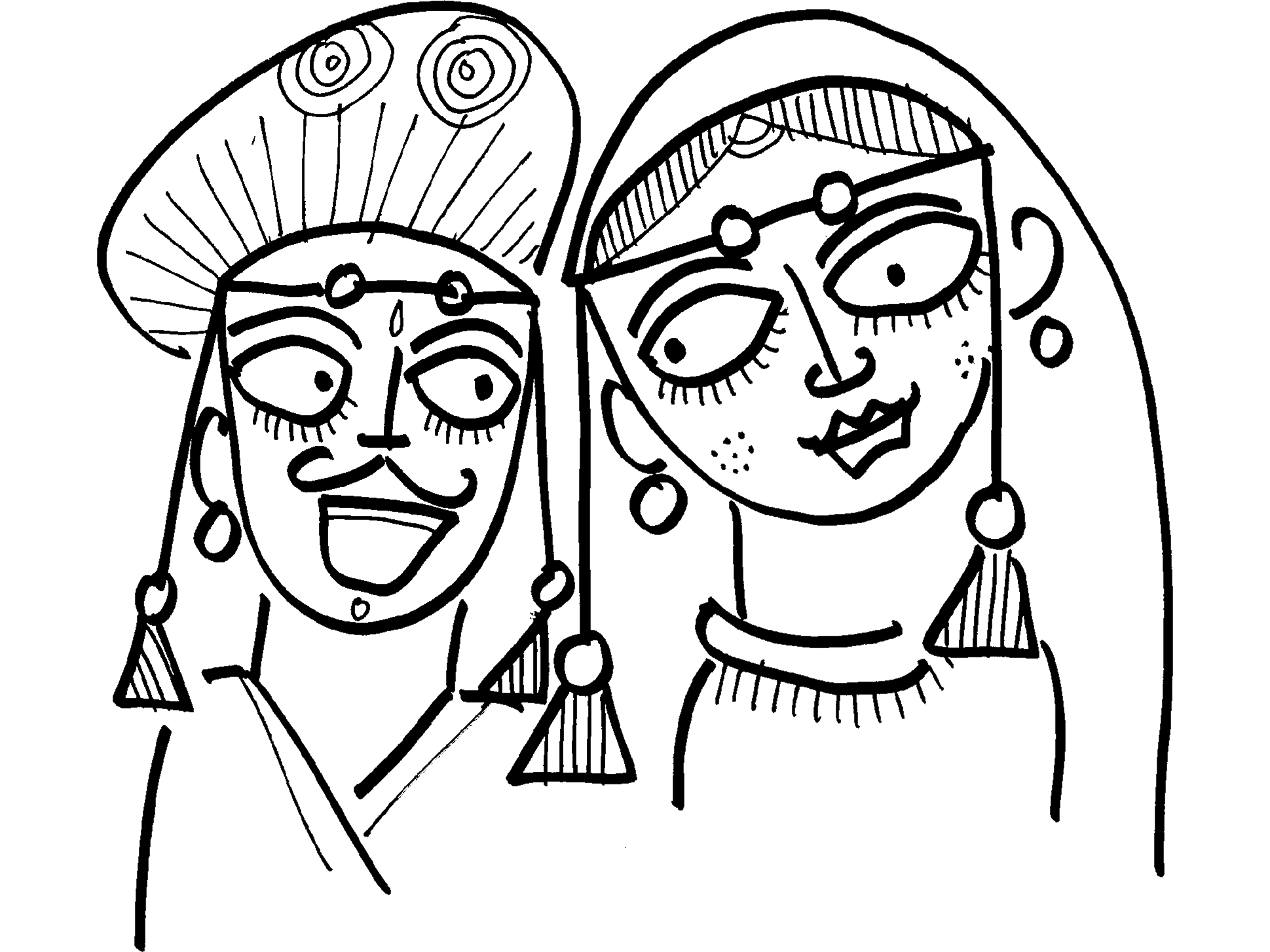

In all probability, these are talismans, bringing in good luck into the household. This was a ritual where the matriarch of the household was the grand priestess. This is how she harnessed cosmic energy and brought it into the household. This is how she anchored divine grace to the house. This was a ritual that she did on her own, without the support of any men or priests. But to do this, there were rules. She had to be a married woman with children. Widows were not allowed to do this and virgins could only support their mothers. Only male priests were allowed to make a rangoli but only as part of a ritual; the rangoli was used to mark out the sacred space where the rituals were performed. This was different from the woman’s rangoli that transformed the house into a sacred space.

Many are of the opinion that the rangoli or kollam is what later transformed into Tantrik mandalas and yantras. Or maybe the process was the other way around. These mandalas and yantras used geometrical forms to represent various gods and goddesses, various natural spirits. A downward pointing triangle represented woman; an upward pointing triangle represented man. A circle represented nature while a square represented culture. A lotus represented the womb. A pentagram represented Venus and the five elements.

Typically a Rangoli begins with a grid of dots being made. The more the dots, the more elaborate the patterns. Given the same grid, different women would see different patterns in it, and draw accordingly. So if one walked down the village street, one would find different households with different patterns.

Different households were run by different women and each woman had her own identity and her own sense of aesthetics which she expressed each day in her Rangoli. While the grid of dots united them all, as did the ritual of making the Rangoli, the specific pattern reminded all of the differences. Every woman did her best but no one compared or tried to turn it into a competition. The point was not to be better than others but to be the best as one could be, for one’s own house. Through these beautiful but different patterns, generations of Indians were taught to be tolerant, to enjoy other people’s patterns and enjoy one’s own, without being judgmental.

Just by looking at the pattern one could determine the mood of the household. Daily patterns indicated discipline. Beautiful patterns indicated joy. Elaborate patterns indicated focus and dedication. Shoddy patterns indicated a bad mood, a fight maybe the previous night. Absence of a pattern meant something was amiss in the household. The Kollam serves almost as a message board of the household.

Once in a while, the patterns were fixed as during festival times. Then the women had to set individual creativity aside and align to the demands of culture or tradition. Those were the days when the women were part of a larger whole. The village rules became household rules.

The Rangoli was never permanent. It was wiped off each morning, reminding all that things change. Yesterday’s bad mood can be become tomorrow’s good mood. Bad patterns can give way to good patterns. The household changes and so do its patterns. People learn and grow and with that patterns become more confident and more joyful.