Published in Speaking Tree, ToI, on 12 Dec 2013.

The puranas say that Manu was the first leader of manavas — people who possess manas or imagination — that is, humans. In every age there is a Manu who writes the Manu Smriti, code of appropriate social conduct for humans. The first Manu Smriti established the caste system and validated practice of untouchability and seeing women as being inferior to men. We rejected it, and rightly so.

The Constitution, the new Manu Smriti, rejects homosexuals. At least, that is what the Supreme Court Judgement on IPC 377 seems to suggest in spirit, if not letter.

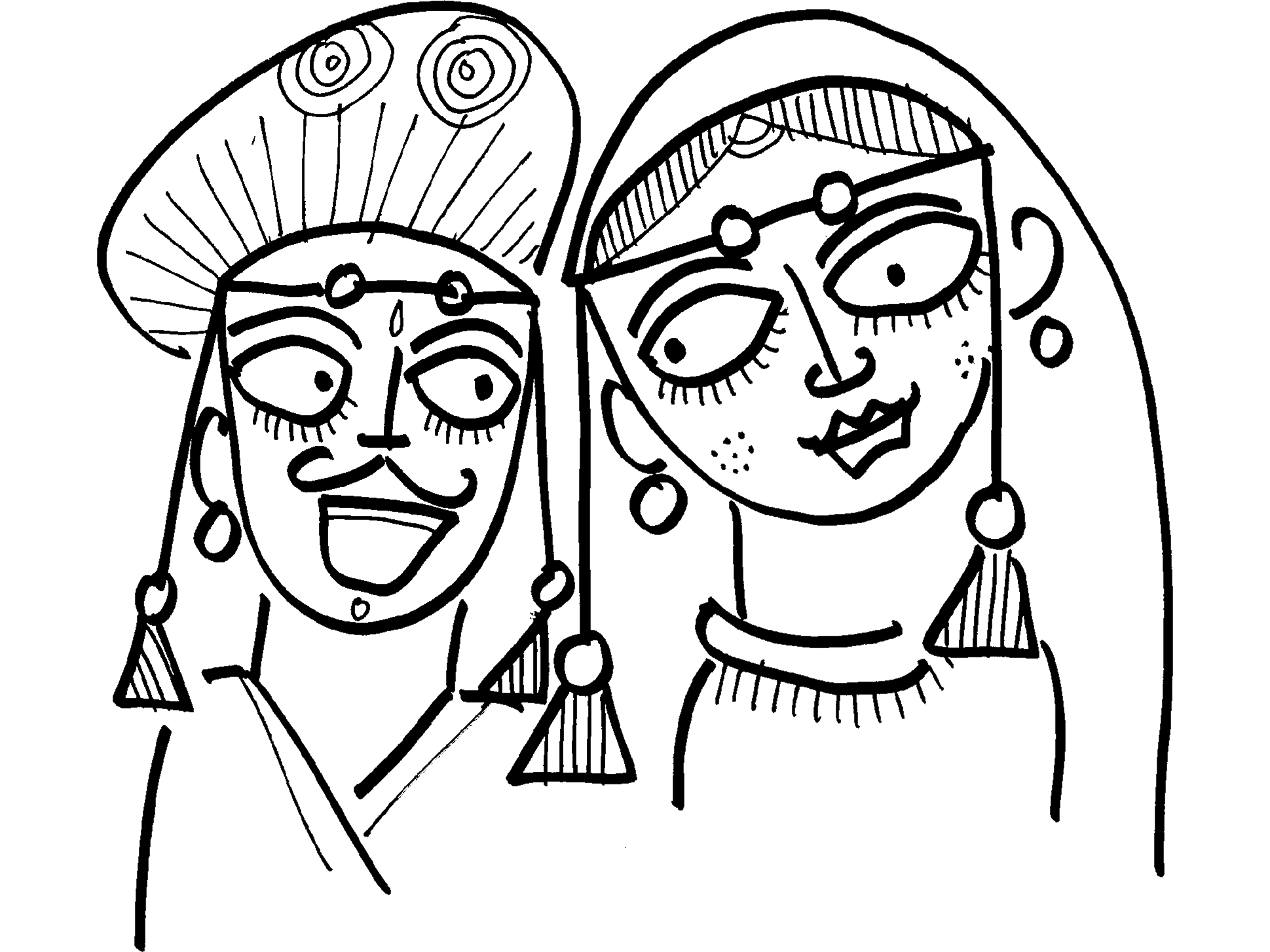

From a procedural point of view, we can argue that Shikhandi is not homosexual. Never mind that in Vyasa’s Sanskrit Mahabharata she is described as being born a woman, raised as a man, given a wife who turns away from her in disgust, forcing her to acquire male genitalia from a yaksha called Sthulakarna.

Was Shikhandi male or female? What will Shikhandi’s physical intimacy with a partner be construed as — homo or heterosexual? But Shikhandi’s very existence would be invalid in India going by the SC judgement that criminalises those with a different sexual orientation.

In the Mahabharata, Bhisma refuses to raise his bow against this ‘non-man’. But Shikhandi rides proudly on Krishna’s chariot, and enables Arjuna to bring the old warlord down, with Krishna’s blessings. And as he lies in bed, Bhisma tells the Pandavas stories of Yuvanashva, the man who accidentally became pregnant by drinking a magic potion meant for his wives, and Bhangashvana, who lived his life both as man and woman, and so had children who called their parent both as ‘father’ and ‘mother’. These ‘queer’ narratives are meant to educate the Pandavas as they prepare to become the next generation of kings.

Indic temple art — including in Konark, Kanchipuram and Thiruvanantapuram — display women in different stages of undress in passionate embrace. Platonic, lesbian — or simply designed to titillate men?

Amongst the many costumes of Krishna in Nathdvara, Rajasthan, is the stri-vesha, where he wears woman’s clothes, remembering his mother and his beloved, Radha, and his form as Mohini. In Mathura, Shiva is Gopeshwara. The mask on the Shivalinga is decorated with female accessories, to participate in Krishna’s raas-lila. Perhaps these were affectionate acknowledgement of transgender realities.

In their writings, Dnyaneshwar and Tukaram address Vithal — Krishna to most Maharashtrians — as ‘Vithai’ or Mother Vithal; God is not Father but Mother, for in love and devotion, gender is sublimated. Such transgressive ideas can indeed be extended to romantic and sexual love. Many male devotees see themselves as lovers of God who they view as male while they express their longing in feminine terms. Are these mere metaphors or an acknowledgement of transgressive desires? Are they only limited to devotional spaces? Can they extend to laws of modern society that can then look beyond gender, at emotions, and allow consenting adults to make love in private?

Why hinder the mind’s expansion? The Upanishads refer to God as Brahmn to indicate that manas, mind, can brah, expand. But we choose to stay Brahmins, followers of Brahma, never quite expanding, digging at our heels, arguing the right to stagnate, even regress.

In the eighth century, Tamil poet Nammalvar wrote:

“We here and that man, this man,

and that other in-between,

and that woman, this woman,

and that other, whoever…

…being all of them, he stands there.”

The verse so wonderfully makes room for the entire spectrum of humanity. So different, is it not, from India’s Supreme Court today?