Published in Corporate Dossier, Economic Times on 11 Dec, 2009.

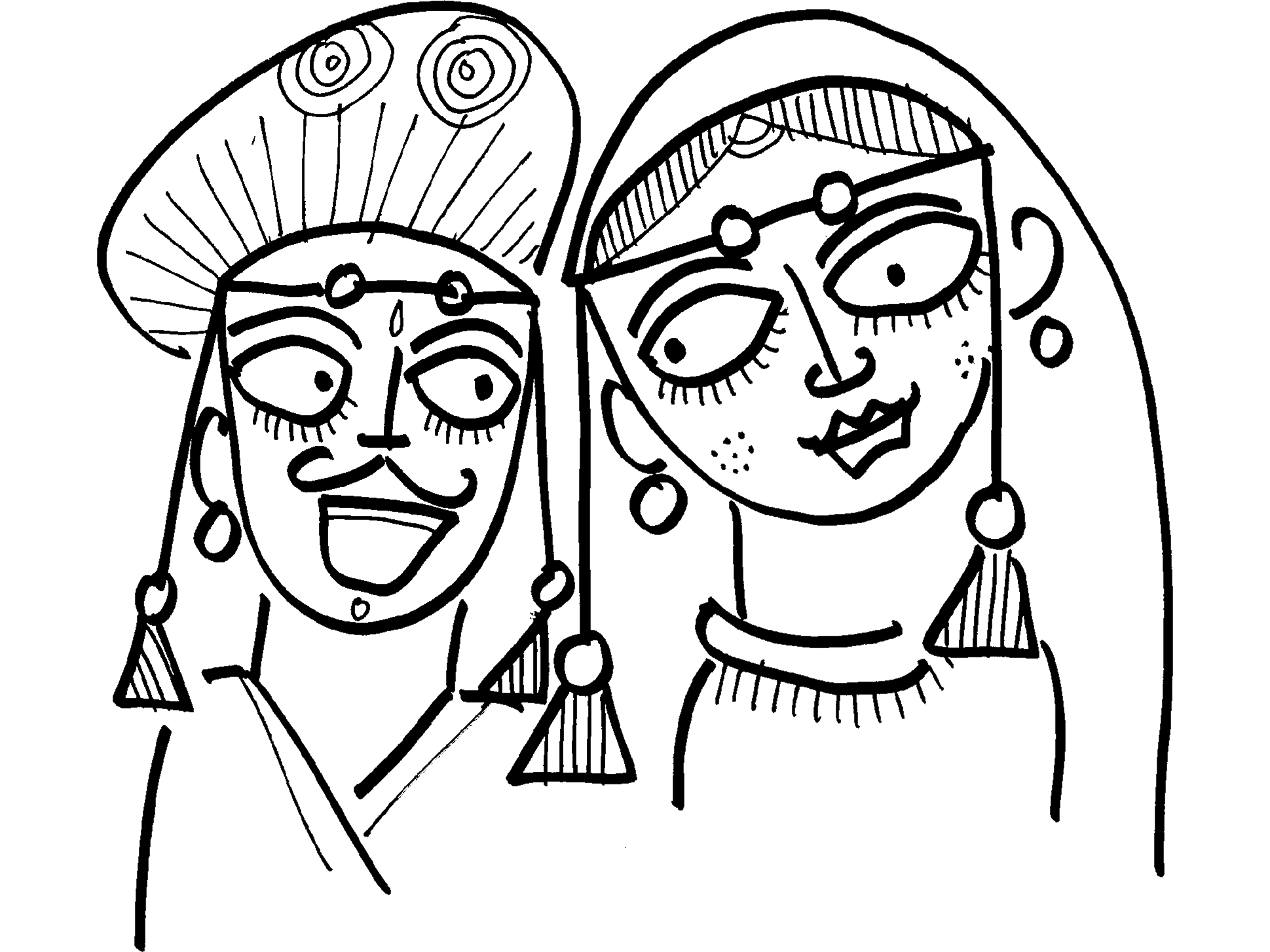

In ancient India, the key ritual of society was called the yagna. It involved setting up of a fire altar into which oblations of ghee were poured to the chanting of hymns. The ritual was meant to benefit the community. The leader of this community was the Yajaman, or the patron. He initiated the yagna and it was he who invested in it. He provided the wood for the fire, the offerings for the flames and it was he who paid the priests their fee. All offerings were made by him and each time the offering was made, he would say, “Svaha”, meaning ‘so I give’. If the yagna was successful, the deity being invoked would appear. This was the Bhagavan and he would offer a boon or blessing. When the Yajaman made his wish known, the Bhagavan would say “Tathastu”, meaning ‘so it shall be’, and leave. The Yajaman was the prime beneficiary of the yagna, and he shared it with the entire community. This sharing with the community made him the leader of the community. The ritual was conducted by a Rishi who had no stake in the process. He was merely an enabler. At the end of the ritual, the Rishi received his fee, the dakshina, and left the yagna-shala or the sacrificial hall.

Yagna is a metaphor for a process where there is an input (Svaha) and an output (Tathastu). As is the Svaha, so is the Tathastu. As one sows, so does one reap! As any data warehousing expert will say: rubbish in leads to rubbish out.

The corporate world is full of processes. Yagnas are taking place in the conference rooms, in the board rooms, in meeting rooms, in town hall meetings, in brain storming sessions, in review meetings, in client interactions. But there is one problem. No one is sure, who is the Rishi, who is the Yajaman and who is the Bhagavan.

The commercial director of a company felt the need for a content management software. He spoke to the IT director and after a whole series of discussions and debates, funds were approved by the MD for the software. The sales director was made responsible for setting it up. And IT department was made responsible for training the executives. That is when the problem began.

No one knew for whom the program was, who would benefit from it, who would have to enter data in it, who would have to work with it and why was it actually needed. Of course, the software firm hired to do the job had a whole set of forms that if filled correctly would answer all these questions but who had the time to fill up those reams and reams of papers. Who knew the answer? The people asking the questions were only doing so to complete their job. “Just put something in every field of all the forms; no one cares what is actually written, expect the quality check department,” they said without actually saying so. So something was written, something was filed, a whole series of meetings took place and, in the stipulated period of time, the content management software was set up. Training was also conducted. Participants had to participate because they were told to do so by the boss. They did not know why they were being trained and how the software would impact their lives, if at all. But the training was conducted in the stipulated period of time.

A few weeks later the CFO had to pay for the software and the training. He wanted to check if the software was serving its purpose. What he found was shocking! Yes, the training had been done, the software had been set up, all the stipulated forms had been filled, but no one actually used it. “Don’t ask me,” said the IT director. “Don’t ask me,” said the software company . “Don’t ask me,” said the IT director. “Don’t ask me,” said the sales director. “Don’t ask me,” said the MD. All eyes fell on the commercial director, and he argued, “Excuse me, did we all not agree that that this software was good for us. We all signed the contract, did we not?”

This is not an uncommon occurrence in many organizations, especially large ones. Processes take place with no one clear who is the benefactor or the beneficiary. Everyone just performs the tasks because process demands it. Yes there are process-owners but this has more to do with accountability than ownership. If there is an audit of the process, the process-owner can be questioned — this seems to be his sole role. He does not consider himself beneficiary or benefactor.

Often meetings are held and projects initiated without clarity about who is the Yajaman and who is the Bhagvan leading to action without output.

Every human interaction has a Yajaman (the beneficiary) and a Bhagvan (the benefactor). Yajaman does the Svaha and the Bhagavan, if pleased, provides the Tathastu. Clarity of this thought enables interactions to have fruitful outcomes. This idea is not new, but cultural terminologies such as these add soul to other wise bland functional words.

On investigation, the MD realized that the content management software was for the benefit of his sales staff but the input had to be provided by the marketing team. The IT team and the software teams were merely enablers — the Rishis, who had no stake in the input or output. Once this clarity emerged, a meeting was called. The Yajaman was clearly identified. He had to take the role, not because the MD said so but because it was important. He had an interesting point, “What is the use of this expensive software? Let us check if knowledge exchange between marketing and sales actually takes place by other methods.” An investigation revealed that this did take place by email and snail mail — but the sales men did not actually read what was given. How was the content management software going to change that? The problem was deeper and one that could not be solved by a software. Once the Yajaman identified the problem, a whole series of solutions were thought of, ones that would impact the balance sheet positively and not one that would indulge the fascination of one director for software toys.